Is the reader familiar with the word ‘supernumerary’? Mariner first read the word in his college days reading about ancient Japanese culture instead of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In ancient Japanese culture, there was a ritual celebrating the wisdom and contribution an individual made throughout their lifetime. At a time when the person was retiring or, more accurately, when the person wasn’t part of the mainstream of things anymore, they were promoted to the status of a supernumerary. It was a positive, honorable acknowledgement. A supernumerary was one who was approached for advice in those few times when elderly wisdom was needed.

For the record the dictionary says: supernumerary – “exceeding what is necessary, required or desired.” Today’s use of the word doesn’t seem to capture the same elegance implied by the ancient Japanese.

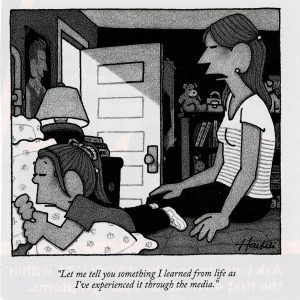

Mariner has declared himself a supernumerary (along with everyone else over 75). A supernumerary does not understand contemporary social principles. Readers know that mariner laments the approaching reality suggested by the Matrix movies – a life totally controlled by artificial intelligence. To this end, mariner must share two cartoons from The New Yorker. The first speaks for itself and represents mariner’s greatest fear:

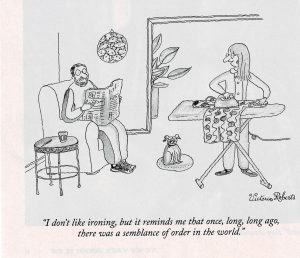

The combined effect of smart telephones, radio, television, computers, internet and social media is that the meaning of life does not come from individual experience. If one was born before this electronic invasion, one remembers discovering life from individual experience. True, life was quite parochial and limited to existential experience but the meaning of life began within an individual’s own brain without the puppet strings of Big Data. The second cartoon speaks to this disparity:

The cartoon speaks to mariner because he was one of the last to have creased jeans with a two-inch cuff. To supernumeraries this cartoon speaks to a time when reality was very much more intimate with human labors and experience. Even the labor of pulling a book from the shelf and turning pages to educate one’s self has been reduced to a thumb scrape or two.

A clear example of disparate social values is the current identity crisis that consumes our daily life, allows wealth to be increasingly unbalanced and causes political wars where there is no compromise. Many say that the only hope is to have unity in our nation. But what does unity mean? What does it feel like? How will citizens behave without populist values? Part of the problem of creating unity is that no one knows what it means to be unified.

Supernumerary folks know. If one experienced World War II that was a time when the nation was unified. America came first – even before citizens chose their groceries, automobiles, vacations, even when to turn all houselights off. Every neighborhood had social clubs for soldiers and sailors; mariner’s father held a weekly dance for the military from Fort Meade and the navy crews in Baltimore harbor. Good cuts of meat were not available in grocery stores because the meat went to the Armed Services. Gasoline was limited to three gallons per month. Women were the majority in factories. Enlisted men had free seats on trains.

Are the younger citizens ready for unity? Can they put aside their populism? It took a world war to unify the United States. There is another war today but it is not bullets. It is climate change, complete restructuring of society and jobs and creating the reality implied by phrases like “All men are created equal.”

If one is not a supernumerary, one has no frame of reference for the responsibilities of national unity.

Ancient Mariner